Image 1 of 2

Image 1 of 2

Image 2 of 2

Image 2 of 2

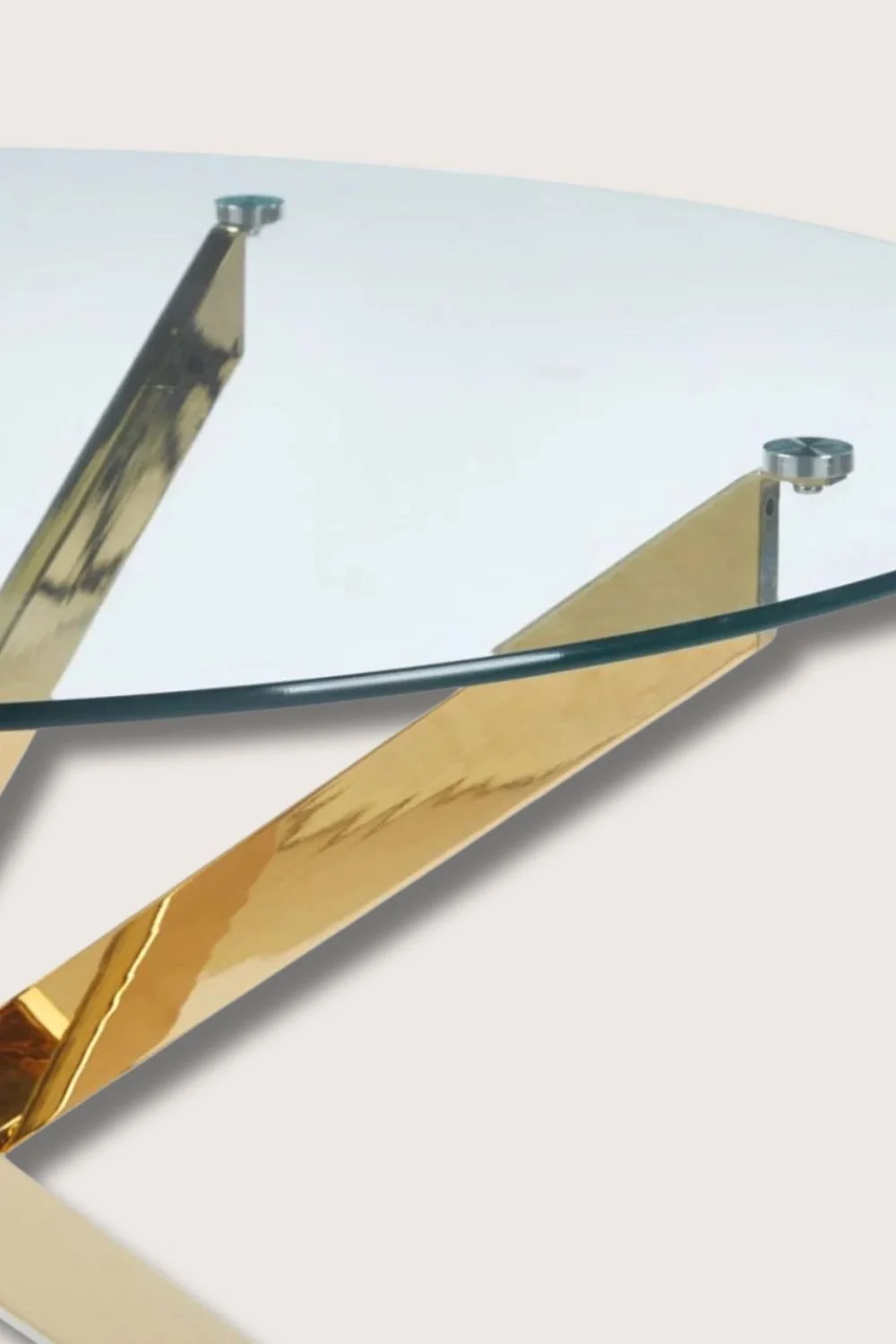

Mandela Dining Table

Details

The Mandela Dining Table is a piece that promotes coming together and conversation. Perfect for a small dining area or kitchen, seat four around this modern pedestal table that garners attention with its unique silhouette. This versatile table can also be used in a home office as a conference table or desk.

Editors' Note

This collection is named in honor of Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela, former President of South Africa and longtime figure in his nation’s struggle for equality. Born in Mvezo, South Africa in July of 1918, Mandela was the son of Nonqaphi Nosekeni and Henry Mgadla Mandela. His father was the leader of the Madiba clan as well as a grandson of King Ngubengcuka of the abaThembu and chief councilor to the paramount chief of the Thembu, his cousin, King Jongintaba Dalindyebo. It was to Dalindyebo that Mandela would go to live with after his father’s death in 1930, moving from the family’s home in Qunu to take up residence with the king in Mqhekezweni. Throughout his childhood, Mandela was educated at several institutions, graduating from Healdtown Methodist Boarding School in 1938 before joining the king’s son, Justice, at the University of Ft. Hare in the Eastern Cape. At the time, Ft. Hare was the only university in the nation to admit Black — meaning African, Indian, or Coloured — South Africans. Leaving school before graduation due to tensions with the administration surrounding a student election, Mandela convinced his family to allow him to live in Johannesburg after he and Justice both fled to the city following their refusal of arranged marriages set by the king. There he met Walter Sisulu, who introduced him to the African National Congress (ANC), which Mandela joined in 1944, becoming acquainted with Ashley Mda, Oliver Tambo, Anton Lembede, and other young intellectuals who spearheaded the formation of the ANC Youth League (ANCYL). Other figures that influenced him at that time were I.C Meer and J.N Singh, activists involved with the Indian Congresses of Natal and Transvaal. Deeply infused with the philosophy of Mahatma Gandhi, the congresses organized a passive resistance campaign in 1946 that was strongly influential on the direction of the ANC. Despite such efforts, however, by 1948 the South African National Party introduced its platform of total segregation called Apartheid (“apartness”). Throughout the 1950s, Mandela’s involvement and influence grew. In 1952, he was elected deputy national president of the ANC as well as president of the Transvaal chapter. Still the power of apartheid grew despite efforts to overturn its policies. By that same year the segregation of the nation was so complete that non-Africans were required to obtain government permits before entering a designated African area. Over the two years that followed, the Defiance Campaign, which began with violating the permit rule, saw thousands of ANC members imprisoned. It also grew the ranks of the ANC to as many as 100,000 before 1954 and Mandela’s leading role in the effort established him as a trusted figure. Yet as the threat of a government ban loomed, the ANC went further underground, and despite the organizations efforts to prevent it, Mandela himself was arrested and imprisoned more than once. One arrest, under the Suppression of Communism Act, came in December of 1952, the same year that he opened the nation’s first African run law practice with Oliver Tambo. The arrest came with a ban that would prevent Mandela from openly interacting with the ANC for several years. He was arrested again in 1956 with 155 other members of the Congress Alliance leadership — men and women of all colors — and tried for treason over a course of nearly five years. These years also saw schisms and splits form within liberation groups as perspectives diverged, particularly around the philosophy of Africanism and the issue of non-African involvement in African liberation movements. 1960 marked a major turning point, both for Mandela and the nation as a peaceful protest planned on March 21st by the Pan Africanist Conference (PAC) — a competing organization which broke away from the ANC in 1959 became remembered as the Sharpeville Massacre. Government troops opened fire on the protesters, killing 69 people and wounding upwards of 200, with many being shot in the back as they fled. Mandela was one of several thousand political activists detained in the immediate aftermath, and by April, both the ANC and PAC were banned. For Mandela, exasperated and hopeless at the government’s constant use of violence in response to peaceful protest, the event broke an already wavering attachment to non-violence. This led — following several subsequent violent acts of suppression by the government — to the formation of the Umkhonto we Sizwe (“Spear of the Nation”) — the paramilitary arm of the ANC. For the next several years, Mandela traveled clandestinely throughout the continent, appearing surreptitiously at conferences, and meeting with leaders and other political activists in nations such as Morocco, Ethiopia, and Algeria. In addition to exchanging ideas and strategies for resistance and liberation at these meetings, Mandela also received military training in anticipation of a phase of armed revolt against Apartheid. The discovery of personal materials documenting Mandela’s travels, training and strategies for guerrilla war led to the 1963 Rivonia Trial, at which Mandela, already imprisoned, was tried alongside several comrades and ultimately sentenced, in 1964, to life in prison. Through 27 years of imprisonment, Mandela continued to grow in international prestige as a symbol of growing anti-Apartheid sentiment, both in South Africa, and around the world. By 1982, he was the chief figure in an international campaign pressuring South Africa to release all of its political prisoners. For the next several years, Mandela would repeatedly refuse offers of release from South African president, P.W. Botha, on the grounds that each required that he renounce the idea of armed struggle against the government. Nevertheless, Mandela always held out the possibility of further discussion with the government, leading eventually to his meeting with Botha on July 4, 1989 — the first time the two men ever met in person. Later that year, he would meet the nation’s incoming president, F.W. De Klerk. It was De Klerk who, in his inaugural address to the nation’s parliament in 1990, would announce the lift of the ban on the ANC and PAC, and the release of Nelson Mandela and all political prisoners. Greeting the world with a spirit of “peace, democracy and freedom for all,” Mandela resumed his work with the ANC even as unrest in the country continued, including a government assault on anti-Apartheid protesters in March 1990 that wounded hundreds and killed 14. Acting as an intermediary between many parties, Mandela treated with organizational and ethnic leaders, such as Chief Mangosuthu Buthelezi, president of the Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP), while levying demands against the government. In 1991 he succeeded in bringing together the IFP, ANC and PAC to jointly oppose Apartheid, mending the rifts between the latter two organizations. His meeting with American president George H.W. Bush in November of that year further cemented his position as an international figure and leader of his nation. In May of 1994, it was official. Nelson Mandela was elected president of South Africa, marking the end of nearly 50 years of Apartheid. Dedicating his time in office to the causes of rebuilding and reconciliation, Mandela retired from political life after his first term ended in 1999. Nevertheless he continued in his role as an international role model, activist and diplomat, presiding over negotiations following the Burundian Civil War in 2000. He also continued to call upon his own government, lauding them for steps taken in the name of democracy but imploring them to center the needs of the people in policy decisions. Through a series of mounting health issues, Mandela would continue in stages to step away from the world stage, until finally on December 5, 2013 it was confirmed that he had passed away, leaving a legacy of unvarying strength in the face of oppression that continues to inspire today.

Details

The Mandela Dining Table is a piece that promotes coming together and conversation. Perfect for a small dining area or kitchen, seat four around this modern pedestal table that garners attention with its unique silhouette. This versatile table can also be used in a home office as a conference table or desk.

Editors' Note

This collection is named in honor of Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela, former President of South Africa and longtime figure in his nation’s struggle for equality. Born in Mvezo, South Africa in July of 1918, Mandela was the son of Nonqaphi Nosekeni and Henry Mgadla Mandela. His father was the leader of the Madiba clan as well as a grandson of King Ngubengcuka of the abaThembu and chief councilor to the paramount chief of the Thembu, his cousin, King Jongintaba Dalindyebo. It was to Dalindyebo that Mandela would go to live with after his father’s death in 1930, moving from the family’s home in Qunu to take up residence with the king in Mqhekezweni. Throughout his childhood, Mandela was educated at several institutions, graduating from Healdtown Methodist Boarding School in 1938 before joining the king’s son, Justice, at the University of Ft. Hare in the Eastern Cape. At the time, Ft. Hare was the only university in the nation to admit Black — meaning African, Indian, or Coloured — South Africans. Leaving school before graduation due to tensions with the administration surrounding a student election, Mandela convinced his family to allow him to live in Johannesburg after he and Justice both fled to the city following their refusal of arranged marriages set by the king. There he met Walter Sisulu, who introduced him to the African National Congress (ANC), which Mandela joined in 1944, becoming acquainted with Ashley Mda, Oliver Tambo, Anton Lembede, and other young intellectuals who spearheaded the formation of the ANC Youth League (ANCYL). Other figures that influenced him at that time were I.C Meer and J.N Singh, activists involved with the Indian Congresses of Natal and Transvaal. Deeply infused with the philosophy of Mahatma Gandhi, the congresses organized a passive resistance campaign in 1946 that was strongly influential on the direction of the ANC. Despite such efforts, however, by 1948 the South African National Party introduced its platform of total segregation called Apartheid (“apartness”). Throughout the 1950s, Mandela’s involvement and influence grew. In 1952, he was elected deputy national president of the ANC as well as president of the Transvaal chapter. Still the power of apartheid grew despite efforts to overturn its policies. By that same year the segregation of the nation was so complete that non-Africans were required to obtain government permits before entering a designated African area. Over the two years that followed, the Defiance Campaign, which began with violating the permit rule, saw thousands of ANC members imprisoned. It also grew the ranks of the ANC to as many as 100,000 before 1954 and Mandela’s leading role in the effort established him as a trusted figure. Yet as the threat of a government ban loomed, the ANC went further underground, and despite the organizations efforts to prevent it, Mandela himself was arrested and imprisoned more than once. One arrest, under the Suppression of Communism Act, came in December of 1952, the same year that he opened the nation’s first African run law practice with Oliver Tambo. The arrest came with a ban that would prevent Mandela from openly interacting with the ANC for several years. He was arrested again in 1956 with 155 other members of the Congress Alliance leadership — men and women of all colors — and tried for treason over a course of nearly five years. These years also saw schisms and splits form within liberation groups as perspectives diverged, particularly around the philosophy of Africanism and the issue of non-African involvement in African liberation movements. 1960 marked a major turning point, both for Mandela and the nation as a peaceful protest planned on March 21st by the Pan Africanist Conference (PAC) — a competing organization which broke away from the ANC in 1959 became remembered as the Sharpeville Massacre. Government troops opened fire on the protesters, killing 69 people and wounding upwards of 200, with many being shot in the back as they fled. Mandela was one of several thousand political activists detained in the immediate aftermath, and by April, both the ANC and PAC were banned. For Mandela, exasperated and hopeless at the government’s constant use of violence in response to peaceful protest, the event broke an already wavering attachment to non-violence. This led — following several subsequent violent acts of suppression by the government — to the formation of the Umkhonto we Sizwe (“Spear of the Nation”) — the paramilitary arm of the ANC. For the next several years, Mandela traveled clandestinely throughout the continent, appearing surreptitiously at conferences, and meeting with leaders and other political activists in nations such as Morocco, Ethiopia, and Algeria. In addition to exchanging ideas and strategies for resistance and liberation at these meetings, Mandela also received military training in anticipation of a phase of armed revolt against Apartheid. The discovery of personal materials documenting Mandela’s travels, training and strategies for guerrilla war led to the 1963 Rivonia Trial, at which Mandela, already imprisoned, was tried alongside several comrades and ultimately sentenced, in 1964, to life in prison. Through 27 years of imprisonment, Mandela continued to grow in international prestige as a symbol of growing anti-Apartheid sentiment, both in South Africa, and around the world. By 1982, he was the chief figure in an international campaign pressuring South Africa to release all of its political prisoners. For the next several years, Mandela would repeatedly refuse offers of release from South African president, P.W. Botha, on the grounds that each required that he renounce the idea of armed struggle against the government. Nevertheless, Mandela always held out the possibility of further discussion with the government, leading eventually to his meeting with Botha on July 4, 1989 — the first time the two men ever met in person. Later that year, he would meet the nation’s incoming president, F.W. De Klerk. It was De Klerk who, in his inaugural address to the nation’s parliament in 1990, would announce the lift of the ban on the ANC and PAC, and the release of Nelson Mandela and all political prisoners. Greeting the world with a spirit of “peace, democracy and freedom for all,” Mandela resumed his work with the ANC even as unrest in the country continued, including a government assault on anti-Apartheid protesters in March 1990 that wounded hundreds and killed 14. Acting as an intermediary between many parties, Mandela treated with organizational and ethnic leaders, such as Chief Mangosuthu Buthelezi, president of the Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP), while levying demands against the government. In 1991 he succeeded in bringing together the IFP, ANC and PAC to jointly oppose Apartheid, mending the rifts between the latter two organizations. His meeting with American president George H.W. Bush in November of that year further cemented his position as an international figure and leader of his nation. In May of 1994, it was official. Nelson Mandela was elected president of South Africa, marking the end of nearly 50 years of Apartheid. Dedicating his time in office to the causes of rebuilding and reconciliation, Mandela retired from political life after his first term ended in 1999. Nevertheless he continued in his role as an international role model, activist and diplomat, presiding over negotiations following the Burundian Civil War in 2000. He also continued to call upon his own government, lauding them for steps taken in the name of democracy but imploring them to center the needs of the people in policy decisions. Through a series of mounting health issues, Mandela would continue in stages to step away from the world stage, until finally on December 5, 2013 it was confirmed that he had passed away, leaving a legacy of unvarying strength in the face of oppression that continues to inspire today.

Additional Details

Black Dining Table

Color: Black

Material: Engineered Wood

Dimensions: 39.37"D x 39.37"W x 29.53"H

Tabletop Thickness 0.98 Inches

Weight: 57.3 lbs

Weight Capacity: 250 lbs

Care instructions: Wipe with damp cloth

Imported

Made to order

Ships free within the continental US in 3-4 weeks