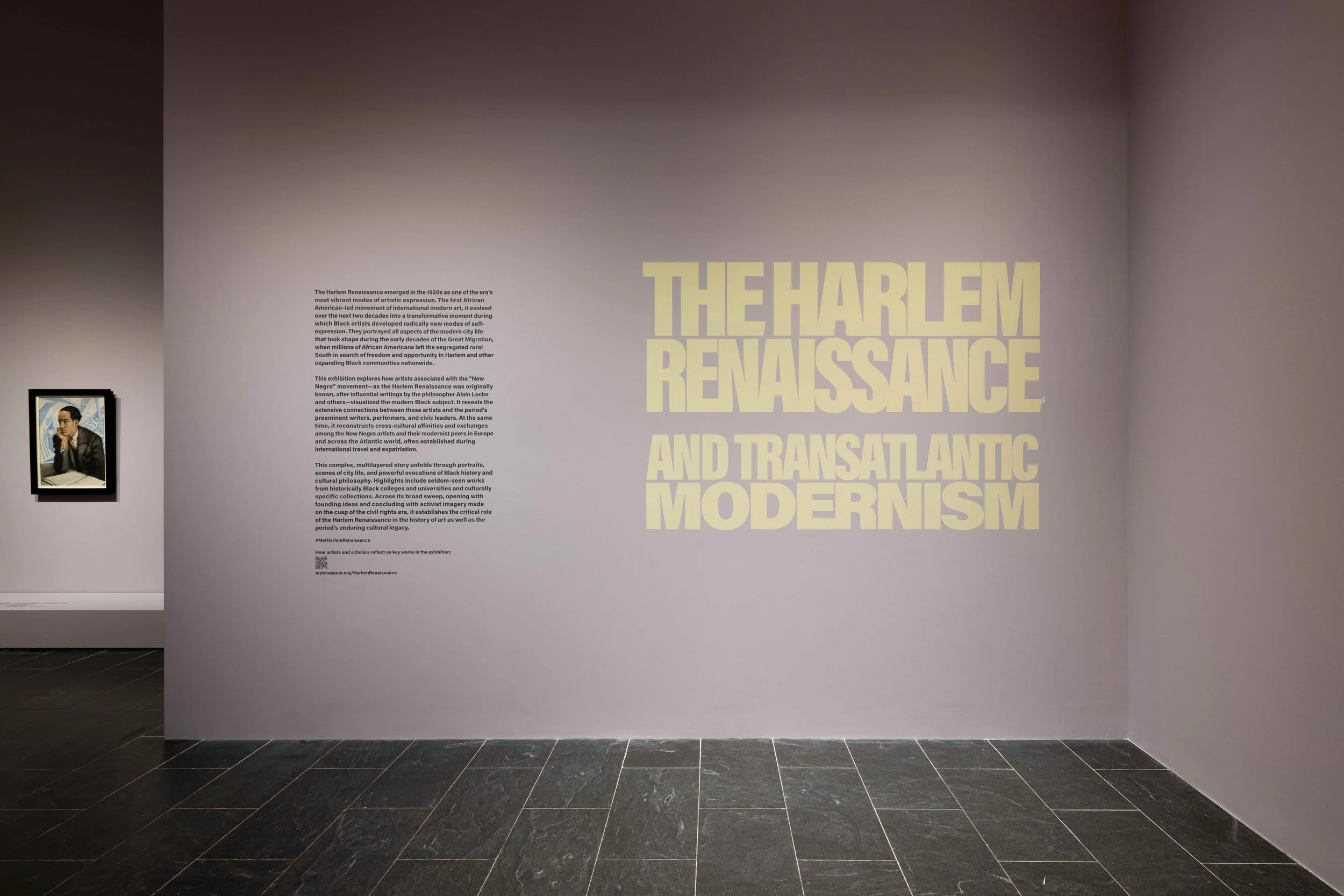

The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism

Photo by Anna-Marie Kellen, courtesy of The Met Museum.

The first exhibition to recognize the Harlem Renaissance as the first African American-led movement of international modern art, "The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism” is on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art from February 25 to July 28, 2024. The exhibition emphasizes the critical role the movement takes in shaping modern Black identity and its far-reaching influence on transatlantic modernism.

Reflecting back on the 1969 exhibition, "Harlem on My Mind: Cultural Capital of Black America 1900-1968," also displayed at The Met, the present exhibition aims to convey a completely different message. While the 1969 exhibition, organized by Allon Schoener, aimed to document life in Harlem through photographs, film, and audio recordings, it was, despite its title, notably lacking in paintings and sculptures by African American artists – an exclusion that drew heavy criticism from the Black community.

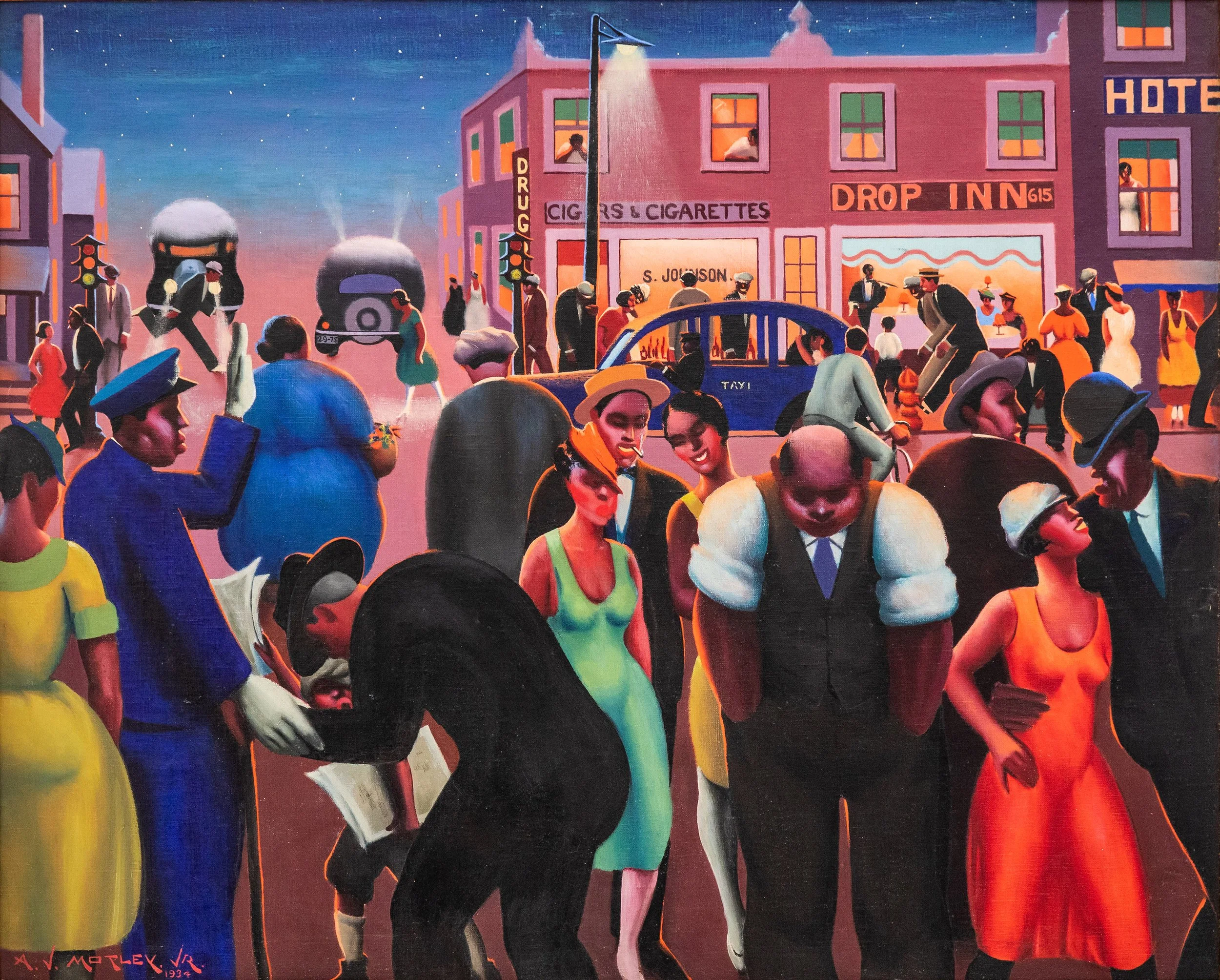

In contrast, "The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism" presents around 160 works of art, including paintings, sculptures, photographs, films, and ephemera primarily by Black artists.The exhibition illuminates how Black artists captured the essence of modern life and the rapid growth of Black urban centers during the 1920s and 1940s, the height of the Great Migration, when millions of African Americans moved from the rural south to urban centers in the north and west.

Max Hollein, The Met’s Marina Kellen French Director and CEO, emphasized the significance of the current exhibition: “This landmark exhibition reframes the Harlem Renaissance, cementing its place as the first African American–led movement of international modern art.” Denise Murrell, The Met’s Merryl H. and James S. Tisch Curator at Large, further elaborated on the impact of these artists, noting how may artists of the New Negro Movement – as the Harlem Renaissance was known in the 1920s – spent extended periods abroad, joining multiethnic artistic circles in Paris, London, and Northern Europe.

Through the collected works, the exhibition delves into the diverse representational styles of individual New Negro artists. Influences cited range from various African art traditions to European avant-garde techniques and classicized academic traditions, themselves influenced by African – specifically, Egyptian – art. Featured artists, many of whom played major roles in the Harlem Renaissance, have their work juxtaposed with portrayals of international Black life as depicted by European artists. The combination is presented as the exhibition examines interactions between Harlem Renaissance artists and their European counterparts, tracing the significant impact of these artists on the developing global lexicon of modernist art.

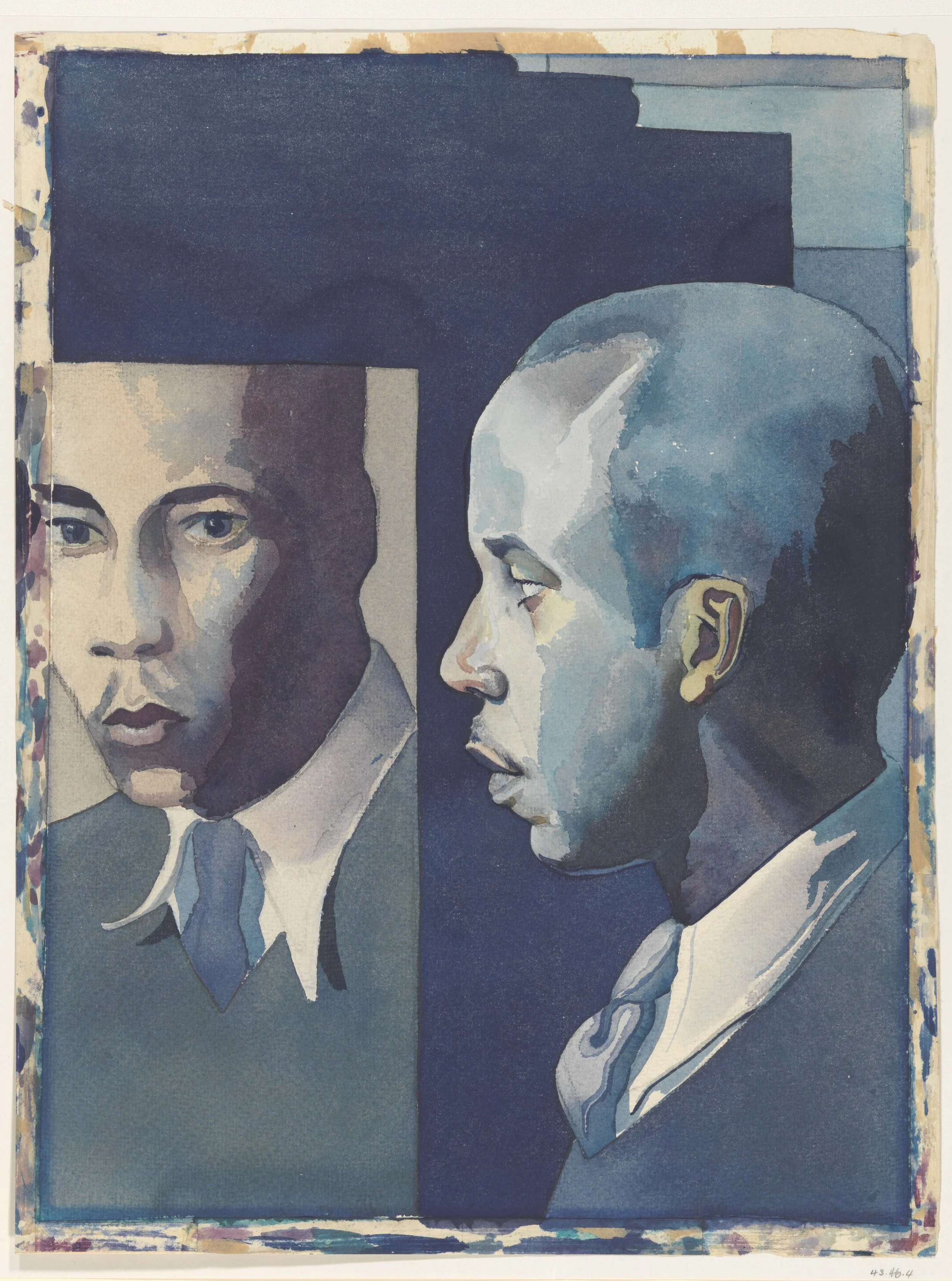

Photo by James Van Der Zee

“Moon Over Harlem,” a later work by Renaissance-era painter, William Henry Johnson. The work commemorates the events of the Harlem Riot of 1943, which began as an African American soldier, shot by a white police officer after intervening in the arrest of a Black woman was mistakenly reported as dead. Though six people would die and hundreds would be injured in the violence that followed, the aftermath forced New York’s mayor to enact policy changes preventing white landlords from price-gouging Black tenants in Harlem.

The exploration emphasizes the unified goal of these artists of portraying all aspects of modern Black life and culture. Starting with the cultural philosophy that gave rise to the New Negro movement, as defined by philosopher Alain Locke, the works featured in the exhibition address diverse social issues such as queer identity, colorism, class tensions, and interracial relations. The exhibit concludes with a gallery dedicated to artists as activists, spotlighting their engagement in the emerging fight for social justice as the New Negro era transitioned into the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 60s. As Denise Murrell poignantly remarked, “It's this idea of the beginning of Black modernity. [The Harlem Renaissance] was the first African American-led movement of modern art [...] the beginning of the modern Black subject that we recognize as part of who we are today.”

Painting by Samuel Joseph Brown, Jr.

The Harlem Renaissance deeply influenced future Black arts movements like the Chicago Renaissance and Negritude. The former emerged as the Harlem movement declined in the 1930s, drawing inspiration from Harlem's cultural vibrancy and nurturing new Black writers, artists, and musicians – including Lorraine Hansberry, Louis Armstrong and Richard Wright – with a focus on racial identity and pride. Similarly, the Negritude movement, led by Aimé Césaire, Léon Damas, and Léopold Senghor, developed in French-speaking Black communities, emphasizing cultural revival and artistic creativity. Both movements, stemming from the Harlem Renaissance, expanded its global influence by celebrating Black identity and challenging colonial and racial oppression around the world.

The exhibit features a significant number of works from the collections of Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs), such as Clark Atlanta University Art Museum, Fisk University Galleries, Hampton University Art Museum, and the Howard University Gallery of Art, emphasizing the crucial role of these institutions in the preservation and advancement of Black art and culture.

More than just an exhibition "The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism" is a celebration of the resilience and creativity of Black artists who revolutionized the way that Black life is portrayed in contemporary art. As we revisit their groundbreaking works, we honor their contributions and ensure their legacies continue to inspire future generations.

Painting by Archibald J. Motley, Jr.